Start Each Day with Pura Vida! Exploring Costa Rican Coffee

In March, I had the opportunity to travel to Costa Rica.

My trip was focused on learning about Costa Rica’s culture and the history of its coffee industry, along with selecting some beautiful coffee for you all to enjoy in 2023! Costa Rica’s geography provides ideal conditions for growing coffee, and its farmers have long been dedicated to producing high-quality beans. In this blog post, you will read about the country’s Pura Vida culture, get an overview of Costa Rica’s coffee regions and a brief history of its coffee industry, cover some trends today, and hear why I think Bear Lake’s approach to bringing you this Pura Vida–infused coffee is so special!

Pura Vida Culture

The term Pura Vida is used throughout Costa Rica. It’s a spirit, vibe, and attitude, and it means “pure or simple life” in Spanish. It’s used as a greeting, a goodbye, a way to defuse a tough situation, and even an exclamation to celebrate a joyous occasion. Pura Vida culture means enjoying life no matter what your circumstances are; it’s about finding gratitude and the idea that life is what you make of it. Now let’s walk through the coffee regions of Costa Rica and see where this Pura Vida –infused coffee comes from.

The Coffee Regions of Costa Rica

Figure 1 – The Eight Coffee Regions of Costa Rica

Costa Rica has eight distinct growing regions, which produce unique flavors and profiles of coffee:

Central Valley

Coffee was first planted here in the 1700s and spread quickly to the other seven regions. Surrounded by San Jose, Heredia, and Alajuela, this region has won quite a few Cup of Excellence awards over the years.

Altitude: 20% at 2,952 to 5,249 feet asl, 80% at 3,280 to 4,593 feet asl

Harvest: November to February

Soil: Andisol

Shade: Ingas, Erythrinae

Tres Rios

This region is just a few kilometers east of San Jose, and its fertile soil is nourished by the Irazu Volcano.

Altitude: 3,937 to 5,413 feet asl

Harvest: November to March

Soil: Andisol

Shade: Ingas, Erythrinae, Musaceae, Forest Trees

Turrialba

The profile of the coffee in this region is enhanced by the Turriabla Volcano. The main city is located northeast of the volcano. This region has collected a few Cup of Excellence awards over the years as well.

Harvest: July to March

Soil: Andisol, Inceptisol

Shade: Erythrinae, Musaceae, Forest Trees

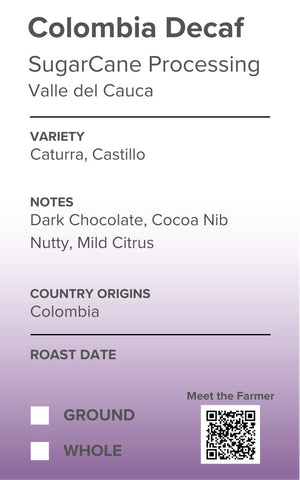

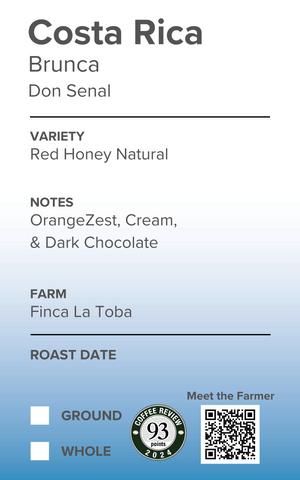

Brunca

The tropical climate of this region gives its coffee a lot of complexity. Located in the south of Costa Rica, Brunca comprises the Coto Brus, Buenos Aires, and Pérez Zeledón cantons. This region has won a few Cup of Excellence awards in recent years.

Harvest: August to February

Soil: Ultisol, Andisol

Shade: Timber trees, Leguminae, Fruit Trees

Guanacaste

Harvest: July to February

Soil: Andisol, Alfisol, Inceptisol

Shade: Ingas, Erythrinae, Musaceae

Tarrazu

This region is the most famous of the eight. It’s known for its high-altitude coffee and massive production, with the largest cooperatives operating here. Tarrazu has collected the most Cup of Excellence awards of any region.

Harvest: November to March

Soil: Ultisol, Inceptisol

Shade: Musaceae, Erythrinae, Fruit Trees

Orosi

This region has a very humid and lush green climate and is known for balanced coffees. It is situated in a valley forty kilometers from Costa Rica’s capital city of San José.

Harvest: September to March

Soil: Andisol

Shade: Erythrinae, Musaceae

West Valley

Harvest: October to February

Soil: Andisol

Shade: Ingas, Erythrinae, Musaceae, Fruit Trees

The History of the Costa Rican Coffee Industry

Coffee production in Costa Rica began in the late 1700s, when the country’s population was around 50,000 people. The first coffee seeds were brought to the country by Spanish settlers and were initially planted in the Central Valley region.

Violent uprising of Indians in Talamanca region, 1709

1800s–mid-1900s

Costa Rica won its independence from Spain in 1821. Some of the initial progressive reforms allowed farmers to earn title to their coffee lands by simply farming coffee. Coffee production was characterized by small-scale, family-owned farms that produced coffee for local consumption and trade. It was considered a luxury beverage, and by the mid-1800s, it was the country’s primary export. A small group of wealthy coffee producers known as the barons del café (coffee barons), rose to power and controlled coffee production. This was a turbulent time, marked by tensions and inequities between the coffee barons, smallholder farmers, and workers.

Figure 11 – Coffee farmers working harvest in the late 1800s/early 1900s

1960s

To deal with these tensions, smallholder farmers formed coffee cooperatives—some of the largest of these were CoopeTarrazú and Coopedota, both of which still exist today. These cooperatives helped the country shift back to a more democratic and inclusive approach to coffee production. In the early years of cooperatives, farmers faced many challenges, including low coffee prices and competing with the larger coffee producers. They persevered, however, and by the 1980s, they had established themselves as top coffee producers in Costa Rica.

Figure 12 – CoopeTarrazú, San Marcos, Receiving and processing area (March 2023)

Trends Emerging Today

Figure 13 – The farmlands of Juanra Montero, Erika Mora, and Ruben Dario, San Marcos, Tarrazu (March 2023)

Today, the population of Costa Rica is around 5.2 million, and the cooperatives continue to work together in order to supply quality commodity coffee to global companies like Starbucks, Lavazza, Nespresso, Peet’s Coffee, and illy. But in recent years, a shift has occurred, with many smallholder farmers processing their coffees themselves rather than bringing harvests to the local cooperatives to be processed. These farmers are working with exporter/importers like Selva Coffee to connect with coffee roasters like Bear Lake Coffee. It’s a win-win, with the farmer getting a higher price and roasters like Bear Lake getting a direct trade relationship with the farmer and higher quality coffees to share with you. During my visit, Selva Coffee connected me with coffee farmer Carlos Montero.

“Times were good then!” he said, and then he laughed and added, “Why do you think all the cars on our farm are either 1970 or 1980 model cars?” Carlos told me that the period of the 1980s through the early 2000s was a grind.

- Quality Concerns: He knows his coffee is of a higher quality than what the cooperatives are focused on or offering to their buyers, and therefore he chose to sell it independently.

- Higher Prices: He could get a much higher price for his coffee by going direct, which allowed him to become more financially sustainable, something he couldn’t achieve working with the cooperative.

- People and Purpose: Farmers like Carlos love people and want to feel connected to a higher purpose. I stayed at his home for four days, and before I left, he said to me, “You are family now.”

Closing Thoughts

It’s truly an honor to work directly with smallholder farmers like Carlos; they care about delivering a higher quality product and building community, and they are invested in the success of their customers and the planet. We are working together in a shared, purpose-driven ecosystem that is driven by us—delivering coffee produced and roasted with love for you to enjoy every day.

I also want to give a special thanks to Selva Coffee for arranging the Tarrazu origin visit. Their team helped me sort through over sixty local farmers in the Tarrazu region. We cupped more than twenty coffees and visited five local farmers, and Selva worked with me to source some amazing 2023 Costa Rica coffee. This Pura Vida–infused coffee will be one of the first coffees offered at our Barronett, Wisconsin, location later this year. It’s our way of wishing you Pura Vida—encouraging you to live your best life!